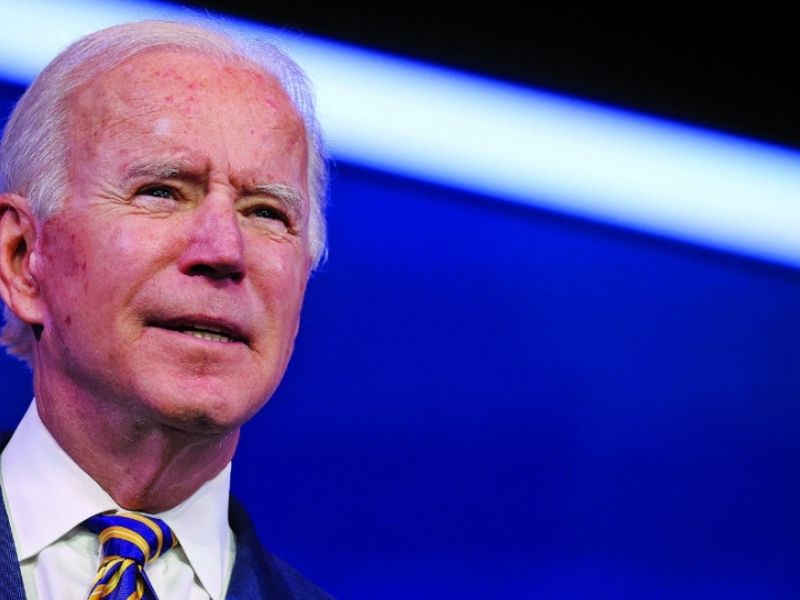

More restrictive regulations and enhanced enforcement are likely on the horizon for the auto industry under President Joe Biden, which could have a significant impact on the nation’s dealers. But maintaining proper procedures and managing compliance programs in the finance and insurance office should ease anxiety provoked by any uptick in federal scrutiny.

Experts from the National Automobile Dealers Association as well as several industry advisers spoke last month on a stack of concerns awaiting the vehicle finance sector and what can be done to prepare as the new administration and Congress settle in and consider changes in their regulatory and enforcement priorities.

“You’ve got the perfect storm of lack of enforcement shifting now with a new administration,” said Clayton Friedman, a partner at Crowell & Moring law firm in Irvine, Calif.

Friedman said the administration’s primary tool is going to be enforcement, with financial practices — including automotive financing — high on the priority list.

“Does a consumer understand what it is they’re paying for their car and how they got to that pricing?” he told Automotive News. “Obviously, we already have regulations out there. Truth in Lending is going to be vehicle No. 1.”

With Democrats controlling the House and taking the narrowest of majorities in the Senate, the Biden administration could usher in stiffer financial regulations that negatively affect dealer-assisted financing, according to Patrick Calpin, NADA’s director of grassroots advocacy.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and the Federal Trade Commission — the two most relevant agencies overseeing auto dealers — are positioned to be led by outspoken critics of certain dealership practices such as dealer reserve and voluntary protection products.

Biden’s nomination of FTC member Rohit Chopra to be director of the CFPB signals that it could be a “much more activist bureau,” Calpin said in February during the virtual NADA Show.

Chopra’s Senate confirmation hearing was held Tuesday, March 2. His nomination is likely to be confirmed.

Meanwhile, Chopra’s colleague Rebecca Slaughter — acting FTC chair who could become the permanent head — also has referred to the auto finance market as “profoundly broken” and has called for a rule-making to regulate dealer reserve.

“Simply put, there’s an attack on vehicle financing underway,” Calpin said.

Senior executives at the American Financial Services Association also said they expected state and federal scrutiny in the auto finance industry to tighten under Democratic leadership, such as taking a closer look at voluntary protection products.

“We’ve heard CFPB may be looking into this,” Celia Winslow, AFSA’s senior vice president, said during the association’s Vehicle Finance Conference held virtually last month. “We spent time over the summer sharing the value of these products with the CFPB, particularly how useful borrowers found them during the pandemic … but we know from past conversations that certain members of Congress view these with a lot of skepticism.”

Paul Metrey, NADA’s vice president of regulatory affairs, also warned dealers of a series of sweeping amendments the FTC proposed to its Safeguards Rule. The proposed changes — which the FTC is expected to take action on this year — could cost an average-size U.S. franchised dealership nearly $300,000 in upfront costs and roughly that amount each year after to maintain compliance, according to an NADA study.

Although dealers are not under the purview of the CFPB, “the FTC does have regulatory authority and has taken enforcement actions against several dealers,” Calpin said.

Aaron Jacoby, managing partner of Arent Fox’s Los Angeles office, where he leads the law firm’s automotive practice, said the industry is already heavily regulated and that many of the “bad outcomes” should be taken anecdotally and not as global statistical evidence of untoward practices.

“It’s not absence of regulation that is causing people to do bad things,” Jacoby said. “It’s bad actors that are doing bad things.”

Still, dealers should be concerned and politically aware of any efforts to severely limit or eliminate dealer-assisted financing, Jacoby said.

They also should assist NADA and their state associations with efforts to argue the position in favor of maintaining dealer reserve, he noted.

Ultimately, if dealers face greater scrutiny and stricter regulations, it could mean fewer choices and higher costs for consumers, according to Marc Spizzirri, senior managing director of B. Riley Advisory Services, a firm that works with lenders, law firms and other companies.

“Many times, overregulation inhibits business and consequently hurts the consumer,” Spizzirri said. “More regulations lead to more burdens on small businesses, raising administrative costs and operating expenses — costs that are ultimately passed along to the consumer.”

Spizzirri said the Biden administration may change the dealer finance landscape with “broader, more restrictive regulations” that could limit consumer options, resulting in a less competitive marketplace.

If dealers are limited in their offerings, “there could be pieces of the population that are left out of an important opportunity to secure financing or purchase warranty products,” said Buddy Dearman, managing partner of the dealership practice at accounting firm Dixon Hughes Goodman.

Dearman said self-audits of a dealership’s stated policies and procedures are crucial. Industry guides such as the NADA Fair Credit Compliance Program and the association’s voluntary protection products policy also should be considered.

“A good first place to start is a review of your own internal policies around arranging financing and all these other products,” he said.

Crowell & Moring’s Friedman also highlighted the value of training on proper procedures to a dealership’s F&I team, which is consistently double-checking consumer-facing documents.

“The more a dealership is able to demonstrate and document that they have compliance procedures in place where they are policing themselves,” Friedman said, “the better off they are.”