KAMINOKAWA, Japan — Japanese automakers, once hailed as electrified-vehicle pioneers but derided of late as reluctant laggards, are finally getting their heads into the global EV game.

The effort begins now, with one of the country’s biggest automakers and one of its smallest lifting the curtain on secretive EV manufacturing hubs that reveal the automakers’ innovative thinking about how to make EVs profitably.

Nissan Motor Co., an EV leader a decade ago that was quickly surpassed by international rivals, is firing up a completely renovated plant to churn out new EVs this winter. And low-volume Mazda Motor Corp. has designed a new line to roll out electrified vehicles.

The factory updates — costing hundreds of millions of dollars — indicate that Japan’s players intend to use their world-renowned expertise in lean manufacturing and creative continuous improvement, or kaizen, to compete in EVs.

The production tricks used by Nissan and Mazda foreshadow the methods compatriots such as Toyota Motor Corp. and Honda Motor Co. likely will deploy as the companies ease into the EV race. Japan Inc. is banking on production prowess to jump-start the country’s automakers as they play catch-up. It is a more cautious approach.

Overseas rivals, including General Motors, Ford and Volkswagen, are building dedicated EV lines designed to churn out mass volumes of battery-electrics, confident in their bets that the market’s EV switchover will be swift and irreversible.

By contrast, Japan’s automakers are engineering next-gen lines to build a mix of EVs and older technologies — even internal combustion vehicles — as they hedge their bets on a more gradual transition to zero-emission vehicles.

The thinking could pay off if consumer demand fails to meet the rosy forecasts of rivals. But it’s a gamble that could easily backfire if EV sales really take off.

“We are in the middle of a transition, and if you go too fast, you could find you have more EV production than you can sell,” said Christopher Richter, chief auto analyst at CLSA Capital Partners Japan in Tokyo. “Having flexibility is probably where you want to be. And what Japan has always excelled at is flexible production. It’s a competitive strength of Japanese auto manufacturers.”

This new Japanese industry path is partly shaped by local realities.

In Japan, about 40 percent of all vehicles sold now are electrified. But only a tiny fraction of total sales are full-electric vehicles. In June, only 1,300 EVs were sold in Japan, just 0.4 percent of the market.

Among those balking at a wholesale shift to EVs is Toyota Motor Corp. President Akio Toyoda. In his role as chairman of the powerful Japan Automobile Manufacturers Association, Toyoda has lobbied for a multipronged approach to electrification that includes hybrids and fuel cells.

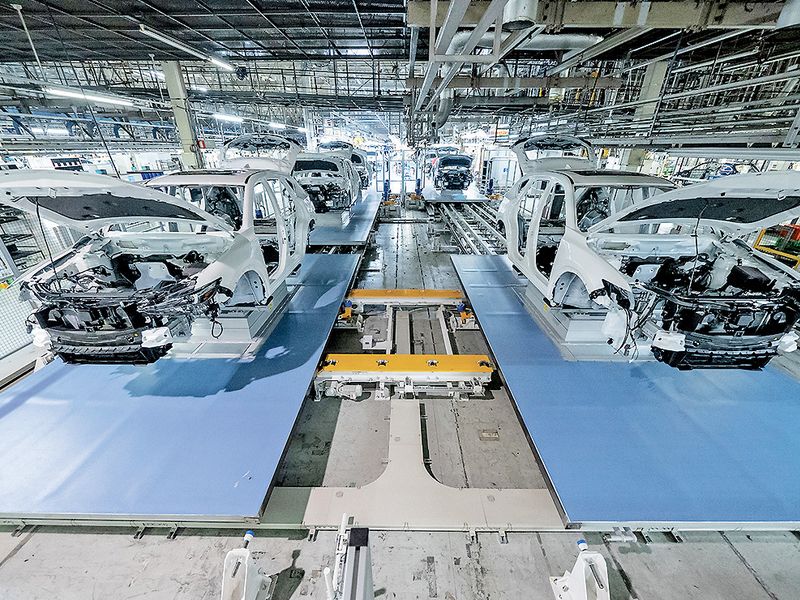

The new manufacturing processes from Nissan and Mazda point a way forward for Japan. Key elements of their production playbooks are ultraflexible assembly technologies, and robots, robots, robots. In conversations during tours of their updated plants, executives could barely contain their delight in dialing down the need for flesh-and-blood workers.

“We need to build a production scheme for next-generation vehicles,” said Hideyuki Sakamoto, Nissan’s executive vice president for manufacturing and global supply chain management. “The first mission is to break away from this traditional, labor-intensive model.”

Robots are seen as a way to improve quality, lower cost and add flexibility.

Indeed, throughout Nissan’s new Intelligent Factory, just north of Tokyo, human workers are few and far between. The scene is much the same at Mazda’s renovated Hofu H2 plant in far western Japan, which completed its EV overhaul in September. At Mazda’s factory, fleets of automatic guided vehicles, or AGVs, shuttle around the factory floor, usurping human jobs.

Both Nissan and Mazda see such automation as unlocking flexible production potential.

At the Nissan Intelligent Factory, housed in what used to be Line 2 of the automaker’s Tochigi assembly complex, it comes in the form of a new assembly technique called SUMO — “simultaneous underfloor mounting operation.” SUMO mounts all of a vehicle’s powertrain components simultaneously from a plug-in palette that is lifted into the body and fitted by robots.

The front, middle and rear of the palette are made of interchangeable modules that can accommodate a multitude of layouts for electric, hybrid and internal combustion vehicles.

At Nissan’s Oppama plant near Yokohama, where the company uses a less-refined mixed production method to make the all-electric Leaf hatchback, workers still need to guide the drivetrain components into place and manually mount them in a labor-intensive process.

Nissan staked a claim to making the world’s first affordable mass-produced EV when it introduced the Leaf in 2010. Since then, Nissan has fallen behind as competitors in North America, Europe and even Japan roll out plans to drop internal combustion altogether. Honda Motor Co., for instance, has plans to make its lineup gasoline-free by 2040.

The Intelligent Factory is critical because it will spearhead Nissan’s second effort to get back in the EV mix by manufacturing the long-awaited Ariya all-electric crossover. But crucially, the factory will also be able to make traditional gasoline-powered vehicles and Nissan’s e-Power series hybrids, to help spread costs across different powertrains during the disruptive transition to EVs.

“To build more complex vehicles, we need to make production more flexible,” Sakamoto said. “Usually, we would need three lines to do this. But here, we have one with high productivity.”

By deploying a host of new production methods, including several world-first techniques, the Nissan Intelligent Factory enables a 10 percent reduction in production costs over older methods, despite building more complex vehicles such as costly, high-tech EVs, Sakamoto said.

Nissan wants all new-vehicle offerings in major markets to be electrified by the early 2030s.

At Mazda’s Hofu H2 plant, AGVs zoom up under the vehicle body and align themselves perfectly for whatever kind of vehicle they are building — with one AGV handling the front of the vehicle, another AGV the back. This allows Mazda to accommodate any combination of long or short vehicles on the same line, with any number of powertrain variants — including all-electric, all-wheel drive, hybrid and even a new longitudinal transmission for rear-wheel-drive vehicles.

Mazda wants EVs to account for a quarter of its global sales by 2030. And by that time, the rest of Mazda’s production portfolio will also employ some other form of drivetrain electrification, from mild hybrid to plug-in hybrid technology.

But it’s a delicate shift for Mazda, a company that long resisted electrification by eking incremental improvements from internal combustion.

Mazda sells just 1.4 million vehicles a year and can ill afford to make high-cost EVs at low volume on dedicated lines. So Mazda’s Hofu H2 line, with annual capacity for 138,000 vehicles, will be making many models.

“We have taken advanced flexible production to the next level,” said Takeshi Mukai, Mazda’s senior managing executive officer for quality, purchasing, production and logistics. “The speed and degree of change in market requirements makes that ever more important.”

Nissan, with global sales of 5.2 million, has a little more leeway. Its Intelligent Factory has annual capacity for 125,000 vehicles and will start production by focusing solely on the Ariya.

Mazda’s Hofu H2 line now handles the Mazda6 sedan and wagon and the CX-5 crossover. But it will soon add the Japanese automaker’s newly developed large-vehicle platform.

That likely will mean building a blitz of new crossovers announced this month that includes the CX-60, CX-70, CX-80 and CX-90. The new nameplates will use turbocharged inline six-cylinder engines and plug-in hybrid systems, as well as diesels and a range of mild hybrids. All told, the new line can handle 150 vehicle variations, including full-electric vehicles, Mazda said.

The factory technology will allow Mazda to pivot according to how the market pans out.

“Flexibility is built in from the planning and design stage,” Mukai said. “That enables us to provide brand-new models while minimizing change points on the manufacturing floor.

“We are ready to handle any increase in electrified models,” he added, “with short lead time and low investment.”