Car designer Moray Callum remembers unveiling his latest project at the 1993 Geneva Auto Show: the Aston Martin Lagonda Vignale concept, a radical, swooping four-door sedan far afield from the Le Mans-winning race cars and James Bond coupes that made the British marque famous.

A proud Callum years later would call the car a crowning achievement of his career.

But that evening, at an industry party aboard a yacht on Lake Geneva, Callum says a former boss introduced him to Robert Cumberford, a protege of the legendary Harley Earl at General Motors Corp., the man who literally invented modern-day automotive design. In the time since his work alongside Earl in the 1950s, Cumberford had built his influence through independent commissions and magazine reviews of the latest models. Callum, thrilled to meet Cumberford and familiar with his work, was keen for his verdict on the Aston.

“Robert told me it was the ugliest car he had ever seen, and had no more comment,” recalls Callum, who until recently was head of design at Ford Motor Co. Callum, a few drinks into his evening at that point, recalls insulting the critic in an outburst he’d soon come to regret. “After my tirade, we parted ways.”

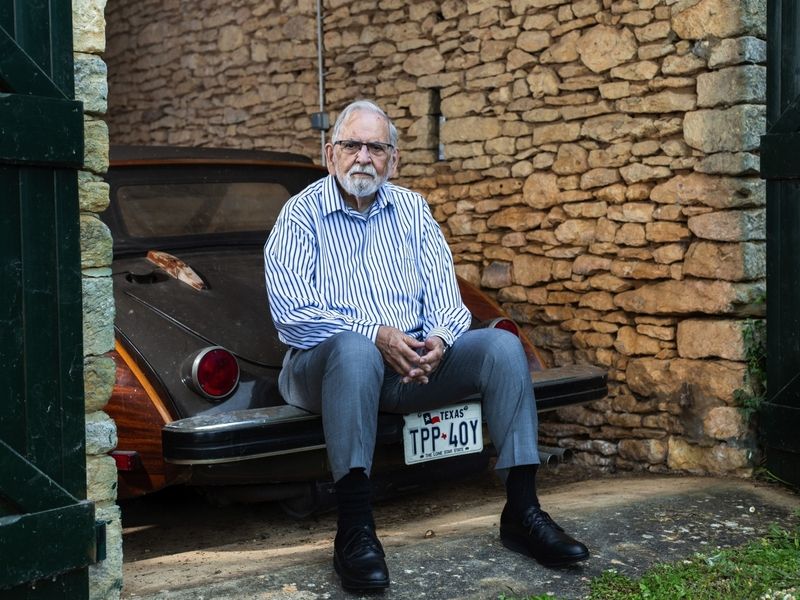

Typical Cumberford: feared, outspoken and respected. For more than a century, automobiles have been key expressions of contemporary culture, but few, if any have written of their evolution with such clarity and authority as Cumberford, now an octogenarian American expat living with his wife, Francoise, for several decades in southwestern France. Firm but fair, Cumberford continues to remain by default the English-speaking world’s dean of automotive design criticism. His career spanned decades, yet his authority on the subject remains undimmed.

Cumberford wasn’t always a critic. He started his career drawing autos himself. He completed only two full cars: the Intermeccanica Italia that married Italian style with Ford V-8 motors, and the Cumberford Martinique that never made commercial production. But he contributed to dozens more. He even imagined and built a prototype Mustang station wagon and pitched it to Ford, which rejected the proposal.

Born in 1930s Highland Park, a working-class Los Angeles neighborhood, to a Scottish father who worked for the city’s Red Car trolley system and a mother from Texas, Cumberford as a child loved airplanes and drew them whenever possible. The love of mechanics soon morphed to cars, and as a teenager he focused on automotive design at Pasadena’s Art Center. He dropped out after refusing to do menial work in return for his scholarship.

Undeterred and emboldened at 19, a confident Cumberford amassed 118 of his drawings and sent the package — unsolicited — to GM’s Harley Earl. His parents pressed him to pursue other careers — medicine, law, teaching, anything. Then came a letter from GM.

“They said they would hire me for $455.50 a month. It was more than my father had ever made in his life,” Cumberford says in one of a series of telephone calls from France discussing his life, cars and more.

Not long after arriving in 1950s Detroit, Cumberford was transferred by Earl into GM’s prestigious experimental Studio X skunkworks, toiling in secret along with Tony Lapine, a young Latvian who’d go on to render the revolutionary Porsche 924, 928 and 944 models. There Cumberford would work on the factory’s first racing Corvette. He says he surreptitiously fleshed out an idea for a four-passenger version of the now-iconic but then-struggling two-seater, anticipating Ford’s Mustang by seven years or more.

“In 1955, they manufactured 700 Corvettes and sold less than half of them. They were talking about just canceling the project,” Cumberford recalls. “Our solution was to do a car that was like what became the Mustang.”

“And when I took the pitch to Harley Earl, he was furious.” Given Cumberford’s nonconformist tendencies and readiness to speak his mind, he lasted less than three years at GM.

That outspoken attitude threads throughout his work. Cumberford recalls a time that he and many other top car designers were asked to pick the best and worst cars in history. He and Giorgetto Giugiaro — famed for work for Alfa Romeo, Ferrari, Maserati and BMW — praised the Citroen DS-19; everyone else panned it.

“Without hesitation or apology he rendered his opinion of new-car designs,” says Joe DeMatio, an editor at Hagerty, who edited and fact-checked Cumberford’s columns for decades. “Robert is not a rushed man. He was often against the grain, panning cars that everyone else seemed to love and praising those that had gone unnoticed. He is a walking, talking, automotive historian, and his deep well of design history informed every review.”

After GM, Cumberford returned to his childhood home of Los Angeles to study philosophy at UCLA before venturing back to the studio. He worked as an assistant for Albrecht Goertz, the American-based, German-born designer of BMW’s legendary 507, a roadster favored by everyone from European royalty to Elvis Presley.

Perhaps the biggest near-miss of his career came while working with Holman & Moody, a North Carolina-based engineering shop contracted to prepare Fords for racing at NASCAR and at the highest levels. There he drew what he calls “a race car that was very simple and easy to take care of, maintain and to race. Ford didn’t want anything to do with it.” The project went nowhere.

Years later he learned what could have been. In 1963, shop founder John Holman approached Chrysler and offered to drop all Ford connections — if Chrysler would underwrite Cumberford’s racer, he says. That approach also went nowhere, and Holman & Moody stuck with Ford.

That Holman & Moody partnership with Ford would in a few short years go on to make racing history. The group engineered a cribbed Lola design that became the iconic Ford GT40 for the 24 hours of Le Mans, hoping for the first time to take a racing trophy dominated by Europeans. Alongside Holman & Moody, Ford recruited a cocky Texan named Carroll Shelby known for winning races and his top driver, Ken Miles, to work on the GT40 project.

Ford won the top-three spots at Le Mans in 1966 with two Carroll Shelby and a Holman & Moody car all crossing the line first. Decades later, Matt Damon would star as Shelby and Christian Bale as driver Miles in the recent film, “Ford v Ferrari.”

Throughout his career, Cumberford toyed with car manufacturing but never broke through. He took a serious look at buying specialist English sports car maker Morgan from Peter Morgan in the 1960s, and made a failed bid to buy Aston Martin from then-owner Victor Gauntlett with his brother, James, in the 1980s. Deep-pocketed Ford prevailed in the competition for Aston.

Earlier in that decade, he formed a company with James, a marketing executive, to produce the Cumberford Martinique, but it, too, ended in disappointment. A 1930s-inspired roadster of unique construction featuring an aluminum body, then-avant garde carbon fiber and structural foam veneered with African mahogany, the Cumberford-designed Martinique used a BMW engine and Citroen hydro-pneumatic suspension. Some $3.5 million was raised for a planned run of 350, at a starting price in 1982 of $124,000 (almost $335,000 today). But the high-profile bankruptcy of the DeLorean Car Co. hampered fundraising. The two original prototypes, one of which appeared on the cover of Car and Driver magazine, still exist.

Whenever not trying to produce cars through the 1970s and 1980s, his Cumberford Design International worked in Europe on behalf of clients including Renault and Citroen. Patrick Le Quément, for many years head of design for Renault, remembers meeting the critic shortly after he’d unwittingly fired him — along with all outside consultants — shortly after assuming the role in the mid-1980s.

“I threw out the baby with the bathwater,” says Le Quément, who’s credited with creating the Twingo and the original Ford Sierra. But he and Cumberford made amends. “What I like about Robert is that he is above all a designer who writes and not a journalist who dabbles in design. He understands, what else can I say?”

“Robert has an opening to the real world, to design in general and socio-cultural evolutions,” he said.

It was around this time — 1986 — that Automobile magazine hired Cumberford as its design critic, a position that to this point had never existed at any similar magazine. And in full disclosure it was there that this author worked alongside him for years.

“He was absolutely honest to a fault and never held back on cutting criticism,” says Jean Jennings, a former editor-in-chief of Automobile. “He terrified designers. He had plenty of enemies but in the end most of his detractors agreed. And of course readers loved him.”

After 30-plus years of writing about cars, Cumberford today returns to his initial passion of airplanes. The industry today is barely recognizable to the one he joined. Sedans are nearly gone. SUVs are everywhere, found even in the hallowed supercar programs of Lamborghini, Aston Martin and soon Ferrari. Even the Ford Mustang has an electric SUV.

He heaps scorn on the recent trend for space-inefficient SUV coupes and increasingly frantic designs, with “everything it’s got stamped into it, a two-inch-thick layer of surface around it, where people do horrible things, including some that look like fish scales, some like horrible nightmares.” He says carmakers should bring back the station wagon and put efficiency above all else.

Unlike many industry veterans, Cumberford bears no ill will toward electric or autonomous vehicles, though he suspects that the two 21st-century technologies are unlikely to enliven automotive design. He quite likes the look of Teslas, including the aggressively angular Cybertruck.

He remains underwhelmed by the fundamental conservatism and pack mentality of most carmakers. Consider the BMW of 20 years ago, when designer Chris Bangle — responsible for the Z3 and Z4 roadsters — persuaded company directors to adopt a higher rear end for the 7-Series of 2001. BMW fans were outraged and called for his dismissal.

Then a funny thing happened. The car outsold its predecessor. Rivals followed. A higher deck gave consumers better aerodynamics and more trunk space. Ever the contrarian, Cumberford admired it.

“The courage to do something new and different is really lacking in the upper levels of all the car companies,” he says. “Truly, the safe thing to do is not much.”

Moray Callum, the designer of the Aston Martin concept car that Cumberford panned in Geneva, later made friends with and was reunited with Cumberford during an industry panel some seven years ago in California. Also on the stage was his brother, Ian Callum, the head of design at Jaguar; Ed Welburn, then GM’s head of design; Shiro Nakamura of Nissan and Andrea Zagato of the famed Italian studio.

Moderating the panel, Cumberford asked the guests to pick the proudest achievements of their careers. Callum chose the Aston Martin.

“I always listened to his input and have certainly learned that it will be his honest opinion that he gives me,” Callum says of Cumberford. “He is unique in the car design world in his ability to write and educate the reader about our business, and that has benefited our profession immensely.”